Transaction Management

Week 11: Reading

Transaction Management

Learning Outcomes

- Learn how to use Multiversion Concurrency Control (MVCC).

- Learn how to manage ACID-compliant transactions.

- Learn how to use:

SAVEPOINTStatementCOMMITStatementROLLBACKStatement

Lesson Materials

Transaction Management involves two key components. One is Multiversion Concurrency Control (MVCC) so one user doesn’t interfere with another user. The other is data transactions. Data transactions packag SQL statements in the scope of an imperative language that uses Transaction Control Language (TCL) to extend ACID-compliance from single SQL statements to groups of SQL statements.

Multiversion Concurrency Control (MVCC)

Multiversion Concurrency Control (MVCC) uses database snapshots to provide transactions with memory-persistent copies of the database. This means that users, via their SQL statements, interact with the in-memory copies of data rather than directly with physical data. MVCC systems isolate user transactions from each other and guarantee transaction integrity by preventing dirty transactions, writes to the data that shouldn’t happen and that make the data inconsistent. Oracle Database 12c prevents dirty writes by its MVCC and transaction model.

Transaction models depend on transactions, which are ACID-compliant blocks of code. Oracle Database 12c provides an MVCC architecture that guarantees that all changes to data are ACID-compliant, which ensures the integrity of concurrent operations on data—transactions.

ACID-compliant transactions meet four conditions:

- Atomic

- They complete or fail while undoing any partial changes.

- Consistent

- They change from one state to another the same way regardless of whether

the change is made through parallel actions or serial actions. - Isolated

- Partial changes are never seen by other users or processes in the concurrent system.

- Durable

- They are written to disk and made permanent when completed.

Oracle Database 12c manages ACID-compliant transactions by writing them to disk first, as redo log files only or as both redo log files and archive log files. Then it writes them to the database. This multiple-step process with logs ensures that Oracle database’s buffer cache (part of the instance memory) isn’t lost from any completed transaction. Log writes occur before the acknowledgement-of-transactions process occurs.

The smallest transaction in a database is a single SQL statement that inserts, updates, or deletes rows. SQL statements can also change values in one or more columns of a row in a table. Each SQL statement is by itself an ACID-compliant and MVCC-enabled transaction when managed by a transaction-capable database engine. The Oracle database is always a transaction-capable system. Transactions are typically a collection of SQL statements that work in close cooperation to accomplish a business objective. They’re often grouped into stored programs, which are functions, procedures, or triggers. Triggers are specialized programs that audit or protect data. They enforce business rules that prevent unauthorized changes to the data.

SQL statements and stored programs are foundational elements for development of business applications. They contain the interaction points between customers and the data and are collectively called the application programming interface (API) to the database. User forms (typically web forms today) access the API to interact with the data. In well-architected business application software, the API is the only interface that the form developer interacts with.

Database developers, such as you and I, create these code components to enforce business rules while providing options to form developers. In doing so, database developers must guard a few things at all cost. For example, some critical business logic and controls must prevent changes to the data in specific tables, even changes in API programs. That type of critical control is often written in database triggers. SQL statements are events that add, modify, or delete data. Triggers guarantee that API code cannot make certain additions, modifications, or deletions to critical resources, such as tables. Triggers can run before or after SQL statements. Their actions, like the SQL statements themselves, are temporary until the calling scope sends an instruction to commit the work performed.

A database trigger can intercept values before they’re placed in a column, and it can ensure that only certain values can be inserted into or updated in a column. A trigger overrides an INSERT or UPDATE statement value that violates a business rule and then it either raises an error and aborts the transaction or changes the value before it can be inserted or updated into the table. Chapter 12 offers examples of both types of triggers in Oracle Database 12c.

MVCC determines how to manage transactions. MVCC guarantees how multiple users’ SQL statements interact in an ACID compliant manner. The next two sections qualify how data transactions work and how MVCC locks and isolates partial results from data transactions.

Data Transaction

Data Manipulation Language (DML) commands are the SQL statements that transact against the data. They are principally the INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE statements. The INSERT statement adds new rows in a table, the UPDATE statement modifies columns in existing rows, and the DELETE statement removes a row from a table.

The Oracle MERGE statement transacts against data by providing a conditional insert or update feature. The MERGE statement lets you add new rows when they don’t exist or change column values in rows that do exist.

Inserting data seldom encounters a conflict with other SQL statements because the values become a new row or rows in a table. Updates and deletes, on the other hand, can and do encounter conflicts with other UPDATE and DELETE statements. INSERT statements that encounter conflicts occur when columns in a new row match a preexisting row’s uniquely constrained columns. The insertion is disallowed because only one row can contain the unique column set.

These individual transactions have two phases in transactional databases such as Oracle. The first phase involves making a change that is visible only to the user in the current session. The user then has the option of committing the change, which makes it permanent, or rolling back the change, which undoes the transaction. Developers use Transaction Control Language (TCL) commands to confirm or cancel transactions. The COMMIT statement confirms or makes permanent any change, and the ROLLBACK statement cancels or undoes any change.

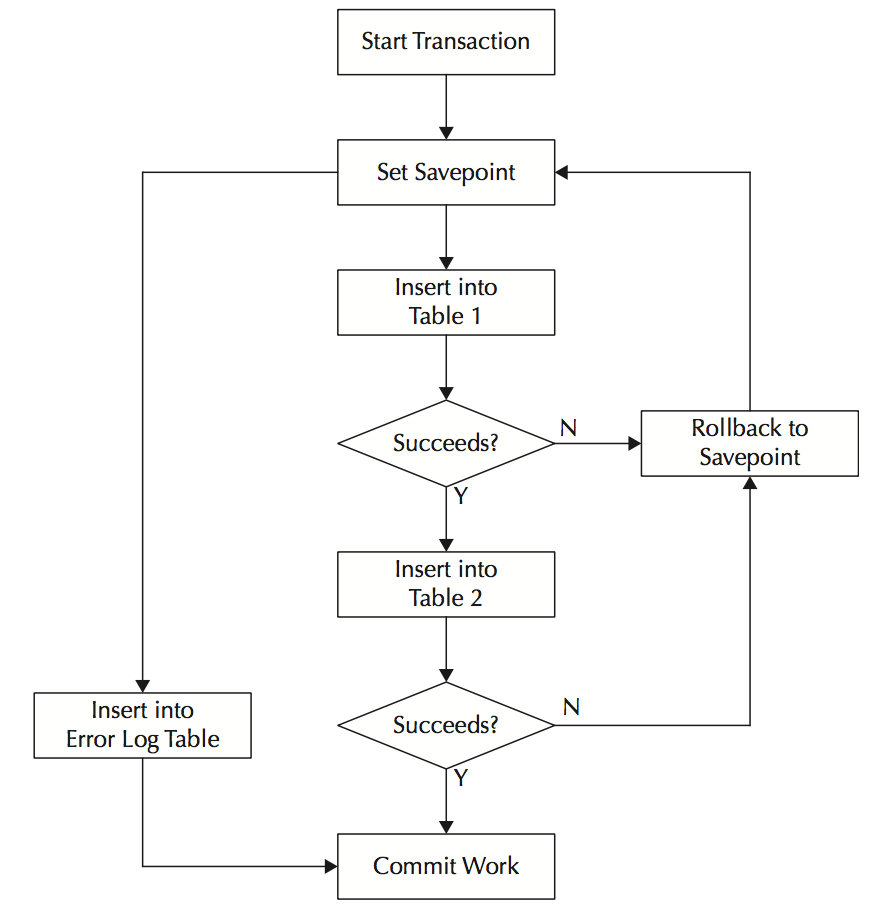

A generic transaction lifecycle for a two-table insert process implements a business rule that specifies that neither INSERT statement works unless they both work. Moreover, if the first INSERT statement fails, the second INSERT statement never runs; and if the second INSERT statement fails, the first INSERT statement is undone by a ROLLBACK statement to a SAVEPOINT.

After a failed transaction is unwritten, good development practice requires that you write the failed event(s) to an error log table. The write succeeds because it occurs after the ROLLBACK statement but before the COMMIT statement.

A SQL statement followed by a COMMIT statement is called a transaction process, or a two-phase commit (2PC) protocol. ACID-compliant transactions use a 2PC protocol to manage one SQL statement or collections of SQL statements. In a 2PC protocol model, the INSERT, UPDATE, MERGE, or DELETE DML statement starts the process and submits changes. These DML statements can also act as events that fire database triggers assigned to the table being changed.

Transactions become more complex when they include database triggers because triggers can inject an entire layer of logic within the transaction scope of a DML statement. For example, database triggers can do the following:

- Run code that verifies, changes, or repudiates submitted changes

- Record additional information after validation in other tables (they can’t write to the table being changed—or, in database lexicon, “mutated”

- Throw exceptions to terminate a transaction when the values don’t meet business rules

As a general rule, triggers can’t contain a COMMIT or ROLLBACK statement because they run inside the transaction scope of a DML statement. Oracle databases give developers an alternative to this general rule because they support autonomous transactions. Autonomous transactions run outside the transaction scope of the triggering DML statement. They can contain a COMMIT statement and act independently of the calling scope statement. This means an autonomous trigger can commit a transaction when the calling transaction fails.

As independent statements or collections of statements add, modify, and remove rows, one statement transacts against data only by locking rows: the SELECT statement. A SELECT statement typically doesn’t lock rows when it acts as a cursor in the scope of a stored program. A cursor is a data structure that contains rows of one-to-many columns in a stored program. This is also known as a list of record structures.

Cursors act like ordinary SQL queries, except they’re managed by procedure programs row by row. There are many examples of procedural programming languages. PL/SQL and SQL/PSM programming languages are procedural languages designed to run inside the database. C, C++, C#, Java, Perl, and PHP are procedural languages that interface with the database through well-defined interfaces, such as Java Database Connectivity (JDBC) and Open Database Connectivity (ODBC).

Cursors can query data two ways. One way locks the rows so that they can’t be changed until the cursor is closed; closing the cursor releases the lock. The other way doesn’t lock the rows, which allows them to be changed while the program is working with the data set from the cursor. The safest practice is to lock the rows when you open the cursor, and that should always be the case when you’re inserting, updating, or deleting rows that depend on the values in the cursor not changing until the transaction lifecycle of the program unit completes.

Loops use cursors to process data sets. That means the cursors are generally opened at or near the beginning of program units. Inside the loop the values from the cursor support one to many SQL statements for one to many tables.

Stored and external programs create their operational scope inside a database connection when they’re called by another program. External programs connect to a database and enjoy their own operational scope, known as a session scope. The session defines the programs’ operational scope. The operational scope of a stored program or external program defines the transaction scope. Inside the transaction scope, the programs interact with data in tables by inserting, updating, or deleting data until the operations complete successfully or encounter a critical failure. These stored program units commit changes when everything completes successfully, or they roll back changes when any critical instruction fails. Sometimes, the programs are written to roll back changes when any instruction fails.

In the Oracle Database, the most common clause to lock rows is the FOR UPDATE clause, which is appended to a SELECT statement. An Oracle database also supports a WAIT n seconds or NOWAIT option. The WAIT option is a blessing when you want to reply to an end user form’s request and can’t make the change quickly. Without this option, a change could hang around for a long time, which means virtually indefinitely to a user trying to run your application. The default value in an Oracle database is NOWAIT, WAIT without a timeout, or wait indefinitely.

You should avoid this default behavior when developing program units that interact with customers. The Oracle Database also supports a full table lock with the SQL LOCK TABLE command, but you would need to embed the command inside a stored or external program’s instruction set.